Under Canadian corporate law, a corporation’s day-to-day activities and decisions are achieved through a board of directors, comprised of individuals who are appointed as directors. If the corporation gets sued or otherwise becomes liable to third parties, the individual directors are generally held safe from personal culpability, since the law acknowledges that they are collectively acting in a designated role as “the operating mind” or embodiment of the corporate entity.

Under this principle, it is the corporation itself that remains at fault for wrongdoings to third parties, not the individual directors themselves.

However, a recent decision by the Supreme Court of Canada modifies that concept in a noteworthy way. In Wilson v. Alharayeri, 2017 SCC 39, the court found that in the face of certain claims by a corporation’s minority shareholder, two individual directors were held personally liable to compensate him for the $650,000 in share-value diminution that resulted from a decision they made in their roles on the board of directors.

The fact involved Alharayeri, who was the former president, CEO and director of a corporation.

Although he had resigned from those positions for unrelated reasons, he remained a significant minority shareholder of a certain class of convertible preferred shares.

Alharayeri’s replacement as president and CEO was Wilson, who also sat on the two-person audit subcommittee of the corporation’s board of directors, along with a person named Black. In their roles on the board, Wilson and Black purported to effect certain changes to the existing corporate share structure, using procedures that were arguably irregular. From a financial standpoint, these changes had the effect of benefiting Wilson and Black as shareholders, while simultaneously diluting the value of the class of shares held by Alharayeri in a significant way.

Understandably unhappy with the changes, Alharayeri exercised his rights as a minority shareholder and launched a court claim for an oppression remedy. He specifically named Wilson and Black, who despite their roles as directors were found by both a lower court and an appeal court to be personally liable for the improper dealing with the shares that resulted in Alharayeri’s losses.

The Supreme Court of Canada affirmed those prior rulings. In doing so, it expounded on the question of when corporate directors can attract personal liability for their actions, including those done ostensibly within the ambit of their directorship duties.

The court began by confirming that a director was not completely immune from personal liability, nor was such liability confined to situations where he or she acts in bad faith or to advance personal interests. Rather, the assessment of whether an oppression remedy should be granted to the objecting party calls for a two-pronged approach. Specifically, the court must evaluate whether:

- The oppressive conduct is properly attributable to the director because of his or her implication in the oppression; and

- The imposition of personal liability on the director is “’fit”’ in all the circumstances.

Looking more closely at the second question, as to the fitness of the remedy, the reviewing court must consider certain additional principles, including the overall fairness of the remedy imposed, its effect on other security holders and whether it goes farther than necessary to rectify the injustice to the shareholder(s). The court must also consider the nature of the director’s breach, as well as the reasonable expectations of the objecting shareholder (or other party bringing the claim for a court-imposed remedy).

Finally, the court also added that the remedy cannot be granted as a means of augmenting a lack of available statutory relief; nor can it be aimed at vindicating family or personal relationships or at serving a purely tactical purpose.

Applying those principles to the facts at hand: As the only members of the board of directors subcommittee, Wilson and Black had significant influence over the board’s decision to modify the shares, which not only benefitted them personally, but also adversely affected the value of Alharayeri’s shares. It was therefore fit to impose personal liability on them in these circumstances, to the tune of $650,000 in losses that Alharayeri had demonstrably endured. The court confirmed that this was a fair way of rectifying the oppressive conduct, while going no further than was necessary to satisfy Alharayeri’s reasonable expectations.

This decision by the Supreme Court of Canada marks an important development in the law relating to directors’ personal liability in connection with the oppression remedy and refines our understanding of this key component of Canadian corporate law.

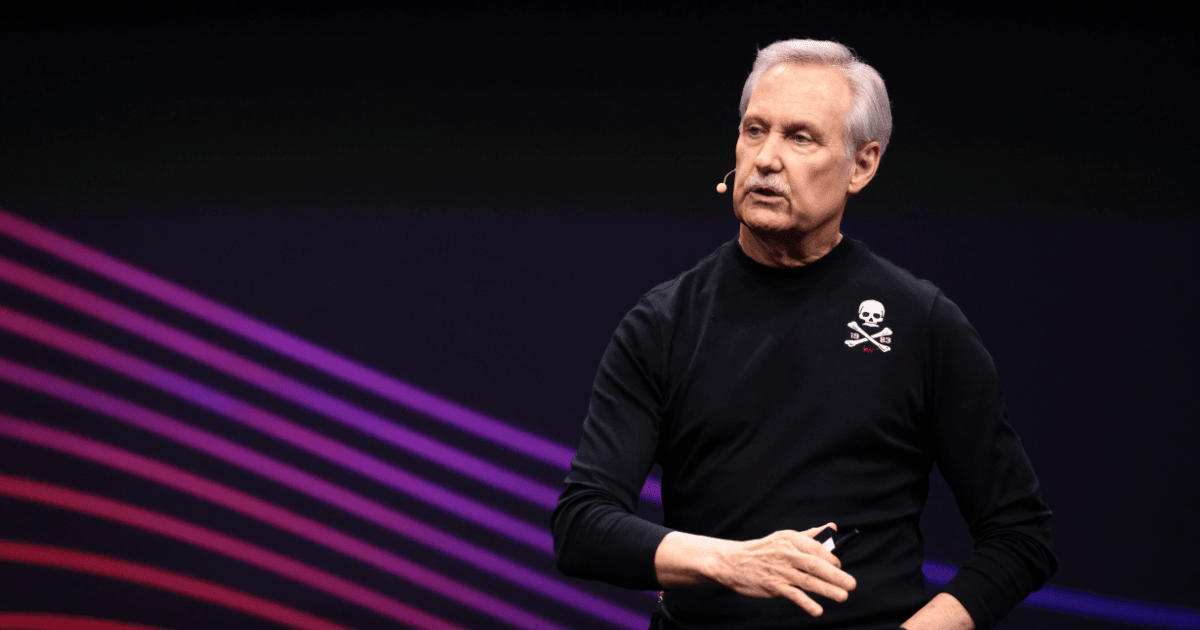

Toronto lawyer Martin Rumack’s practice areas include real estate law, corporate and commercial law, wills, estates, powers of attorney, family law and civil litigation. He is co-author of Legal Responsibilities of Real Estate Agents, 4th Edition, available at the TREB bookstore and at LexisNexis. Visit Martin Rumack’s website.