Canada is not without seismic risk. Just because it hasn’t happened lately does not mean it won’t happen in the future. The quakes in Japan inspired me to contact the Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction (ICLR.org)’s lead seismic expert, Keith Porter, PhD, to discover how prepared Canada is and what the implications to real estate practice might be.

Dr. Porter says, “The New Year’s Day earthquake in Japan feels comparable to the 1994 Northridge earthquake in terms of the total number of people affected at various levels of shaking intensity. I’m seeing no surprises.” The death toll mounts, with warnings of aftershocks. Porter told CBC National viewers that there is a possibility that this is a pre-shock, with a larger earthquake to follow.

Impacts not unexpected

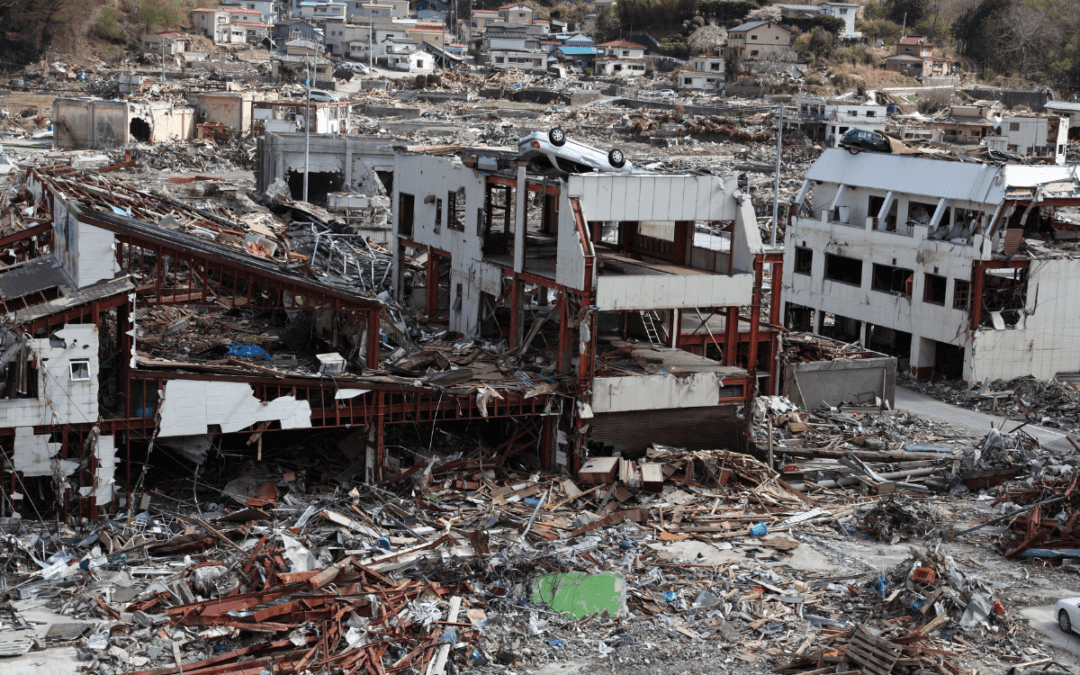

The earth science impacts are pretty much what one would expect from an earthquake of this magnitude and this kind of location, and the performance of buildings, utilities and transportation infrastructure is pretty much as expected. The earthquake happened on the west side of Japan where there are fewer earthquakes — this is the largest earthquake within 250 kilometres of the event in over 100 years.

Japan gets earthquakes and not all that infrequently — they have had a handful within a 6+ magnitude in the last 100 years within 100 kilometres, and about 30 within 250 kilometres. This one was just relatively big.

The buildings performed much as we’d expect, with the heaviest damage happening to traditional Japanese post-and-beam construction, which is very heavy and fragile. Japan has low rates of seismic retrofit to deal with these buildings, Dr. Porter notes. So, it seems many of the collapses are in this type of building.

Modern buildings collapsed

We saw collapses to modern engineered buildings because of liquefaction, just as we have in past earthquakes. There was a seven-story building that seemed to have suffered liquefaction under the foundation. It fell over and entirely rotated 90°, as it doesn’t have the kind of foundation that would prevent this from happening.

This was just like some collapses we saw in the 1964 Niigata earthquake. Then, several mid or high-rise apartment buildings suffered liquefaction failure under the foundation — they rotated over onto their sides.

Lack of tsunami protection led to fires, landslides and more

We tend to look within Japanese earthquakes for damaged nuclear power plants. There weren’t any. We also look for the effects of tsunamis — in this case, there was a meter and a half tsunami. It doesn’t look like there was much tsunami protection along the coast and there was consequent damage.

Dr. Porter explains that while there were relatively few fires this time (about five), it’s not uncommon for fire to be a significant secondary risk. While it was terrible for the people whose homes burned down, there could have been many more.

There were also some landslides underneath the buildings. Modern construction is not going to prevent this from happening.

Lessons to be learned

This month’s earthquake was a serious one, though nowhere near as serious as the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. That said, we still learned some unpleasant lessons and got a clear signal that Japan has to up its game in terms of mitigating vulnerable buildings. There are a lot of people rendered homeless by this, yet it’s all predictable. They’ve had decades to think about solving these problems but they haven’t done so.

Now, that’s not to say that we’ve done a whole lot better in North America. Once the big earthquake comes along in California, I think there will be many more buildings that have been retrofitted. California is doing a better job of fixing its vulnerable buildings.

The difference in Japan

When we think about earthquakes in Japan, we tend to assume that the Japanese are doing much better in terms of new design that makes their buildings more resilient than we do in Canada and the United States. Unfortunately, that’s not the case.

Japan aims for life safety in a rare shaking, meaning it’s a success if you walk out alive and the building doesn’t collapse onto you. But, buildings don’t need to be total economic losses, where many people are suddenly homeless and many businesses are suddenly displaced.

We can do better

While nobody’s doing any better in the United States, Canada or New Zealand, we could. And, it would cost us less in the long run to make our buildings stronger, stiffer and more resilient to earthquakes than we currently do. We know what to do, and how to do it.

I asked Dr. Porter about the kind of foundation that would survive liquefaction. He says it’s either driven piles or drilled piers and what we call a deep foundation. The seven-story building that fell over in Japan looks like it was on what we call spread footings.

When you build with a deep foundation and drive piles into the ground, it tends to reduce the liquefaction potential, and it means the building is founded below the liquefiable soil level. The incremental cost to create a deep foundation when building in a seismic zone seems like a good investment.

What can real estate practitioners in residential resale do?

Dr. Porter has the following advice for realtors: “If you’re selling residential, my advice is to get ahead of the disclosures. Find out, before you put the house on the market, whether it has unbraced cripple walls or lacks foundation bolts. Find out in advance with an inspection and solve the problem before you list. I suspect that if it’s marketed well, it would pay for itself and reduce the challenge of dealing with a negotiation when the buyer does a home inspection.”

How homeowners can reduce seismic risk and maximize their investment

Whether building on a pristine site or modifying an existing structure, building with seismic risk in mind makes sense. It’s often possible to retrofit a house for greater resiliency at a relatively low cost. Dr. Porter also references the ICLR homeowner earthquake guide.

Not only do homeowners and their families benefit from peace of mind, but if they wait until disclosures and inspections when they eventually sell, they may end up giving up a lot more when the buyer says no. I would suspect that in markets where seismic risk is present, like California, seismic retrofit has real market value.

Source: ICLR.org

If your clients own mid-rise apartment buildings, there are opportunities to reduce risk there too. One of the most common weaknesses in apartment buildings is tuck-under parking. This is where the ground floor is like a basement, with parking halfway down and not many walls. These structures collapse in earthquakes. It’s a relatively simple retrofit to correct, though not cheap — probably costing about $15,000-$20,000 per unit. That said, the problem in California is so serious that some communities are mandating the retrofits.

Another risk is the aftermath of fire. When the ground shakes, gas lines and water mains break. When fires erupt, there are road infrastructure disruptions, and if firefighters can reach the fire, water doesn’t always flow. In addition to strengthening buildings and improving their resistance to seismic failure, there are also opportunities to store water for firefighting on-site, using large cisterns.

Maybe it’s best that owners get ahead of things rather than run the risk that they’ll see a big earthquake collapse their building. This can be an investment by a landlord for a multi-unit rental or by a condominium board. I would think this is especially important if you’ve got a client whose real estate portfolio is not diversified.

“Seismic risk reduction may be the most important home improvement they make”

I also reached out to Jessica Shoubridge, founding ED of Understanding Risk BC, who is an expert in natural hazard risk in British Columbia for her thoughts. “This is a financial risk that is not only important to individual British Columbians like me who live in the most gorgeous places in Canada, but it is also considered a financial threat at the national scale,” she says.

“Seismic risk is so catastrophic and current efforts to address it and fund seismic risk reduction are negligible in comparison. For individuals whose largest asset is their home, the opportunity for seismic risk reduction may be the most important home improvement they make.”

Chris Chopik is an influential housing industry innovator and a respected authority working at the intersection of housing, energy, resiliency and natural hazards. Chopik’s work includes an extensive exploration of the future of “Property Value in an Era of Climate Change” (2019) where he examines the financial impact of natural hazards on property values across North America. He holds a Master of Design, Strategic Foresight and Innovation from OCAD University.