Car centric suburban communities have led to a loss of humanity that might be reclaimed in new connected neighbourhoods, futurist Jesse Hirst told an audience in Calgary recently.

Presented by Dream, one of Canada’s largest real estate companies, the event was held to get people talking about how communities can help people connect with each other in their neighbourhoods.

The event was hosted by Todd Talbot, the star of Love It or List It Vancouver. Talbot has strong opinions on the types of homes that should be built in specific areas.

Actor turned real estate industry success story, Talbot believes that a community is a function of the people who live in it. “Community is not just a physical link for people; it is also a social experience. We all crave a genuine connection.”

Trevor Dickie, the vice-president of Dream, has been in the development industry for more than two decades. Dickie introduced the evening, speaking of the importance of staying connected, especially during the current ‘economic softening.’ In the residential and industrial development realms, Dickie stressed that the following are important: strong assets in the bones of development, courage and vision, resources to deliver the product, expertise and talent in those executing the work and passion and perseverance

Dickie and Dream’s goal is to build better communities. Connectivity plays a big role in those communities, according to both.

Amanda Hamilton was one of the three guest speakers. A sought after interior designer in Western Canada, she says the social DNA of a community plays a major role in how people and a community are connected.

The only American on the panel, Joey Scanga is an urban designer and has been with Calthorpe Associates in Berkeley, Calif. for more than two decades. In on trends before they’ve even registered with others, Scanga focuses on how neighbourhoods fit in a region and how the region works with the neighbourhood. He sees a strong connection between land use, transportation and air quality.

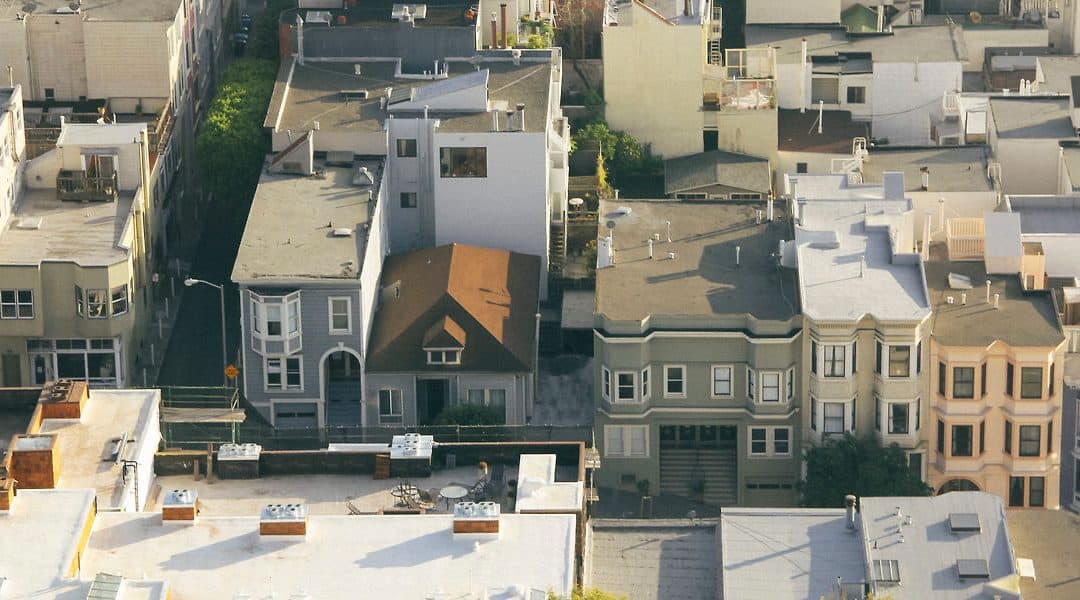

Scanga is leaning away from what he calls ‘auto-oriented developments’, essentially neighbourhoods where the only link between the office, the retail areas, and the home is a car. He’s shifting the focus from parking lots and auto-oriented neighbourhoods to pedestrian-oriented ones in an effort to reconnect people. We need to change the land uses and the way we grow, Scanga says. Beyond the connectivity factor, land use has a bigger effect on environmental factors than most other aspects of development.

Scanga listed a few major things that need to be taken into consideration when planning a development: the region and the neighbourhood, diversity and balance, human scale and conservation and restoration.

Futurist Jesse Hirsh is a big believer in connectivity and says that it is linked to all things: knowledge, education, friends, family, design, everything. “Connectivity is tied to transparency and we are living in an era of transparency.” Hirsch believes that design allows us to take culture and fuse it with technology and that, “Technology is helping us reconnect to humanity.” Our car-centric lives are why we lost our humanity in the first place, he says.

When asked about the issue of investment in community and what drives people to a certain area, Hirsh believes the answers lie in connectivity, walkability, and artists. “When the sum is greater than the whole, that is what makes a neighbourhood great.” For Scanga, it comes back to having a home that functions for the family in it and a community that supports being close to your family. “With so much technology, people strive to be closer to family and friends.”

The trend to more human-centric neighbourhoods that are less car-dependent is already happening. Talbot shared an example of a 400-unit apartment building in Vancouver. The building only has 350 parking stalls for the 400 units. A few years ago, it would have been nearly impossible to sell the last 50 units with no parking stall, Talbot says. Now some buyers don’t even ask about a parking stall.

For a zero car lifestyle, most families would need to live in a city’s core. But as Hirsh pointed out, families are being pushed out of the city centres due to high real estate prices, leaving the suburbs as the only option, which also leaves people car-dependent. “The average commuter in Toronto spends three hours a day in the car,” Hirsh says. “It’s a sad reality that those who live the ‘burbs are car-dependent.

But families with young children can’t afford to live in the inner city, Hamilton says. What’s the solution? One option is to build developments and communities that include all three aspects: office, retail and homes. That way people won’t be chained to a vehicle. Talbot says people who can afford to are moving back to the core when they see that the outer layers of a city aren’t meeting their needs like they thought they would.

Hamilton says it’s about people changing their perceptions of space. “For example, people in the inner city move to suburbia for more square footage but they don’t know what to do with all that space.” Hamilton shared stories of homes where she’d been asked to do the interior design. The homeowners had entire rooms they never used and were clueless as to how to make them function.

In Talbot’s real estate experience, the suburbs have a negative connotation in most cases. “People are not cheering about being pushed out of the core and into the suburbs.” The sterile, isolated neighbourhoods that make up the suburban life aren’t as appealing as they used to be.

Toby Welch is a contributing writer for REM.